Your Results Will Appear Here

Enter your details and click “Calculate BMI”

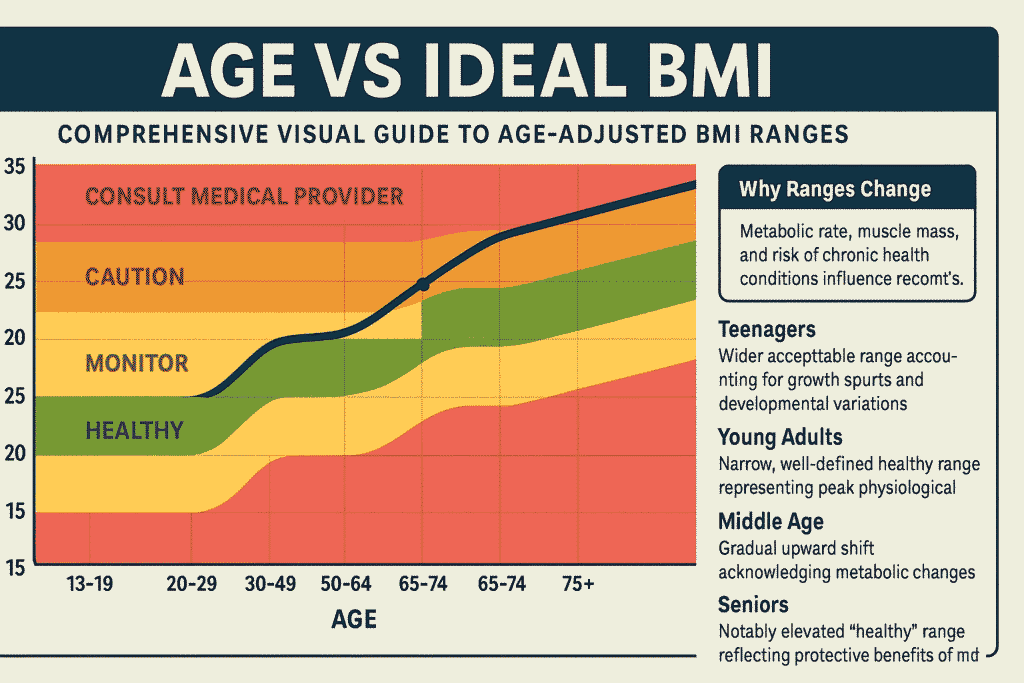

BMI Ranges for Your Age Group

Understanding your Body Mass Index (BMI) isn’t just about knowing the number, it’s about interpreting what that number means for your specific age group.

As we age, our body composition changes significantly, making age-specific BMI calculations essential for accurate health assessments.

Whether you’re a teenager navigating growth spurts, an adult maintaining optimal health, or a senior concerned about age-related changes, this comprehensive guide will help you understand how age influences your BMI and what those numbers really mean for your health.

Why Age Matters for Your BMI

Your BMI tells a dramatically different story at 15, 35, and 65 years old. Understanding these differences is crucial for making informed health decisions throughout your life.

Age affects BMI interpretation through several interconnected biological processes that fundamentally alter how we should view these measurements.

Body Composition Changes Throughout Life

The human body undergoes continuous changes from adolescence through senior years, each phase bringing unique characteristics that affect BMI interpretation:

Teenagers (13-19 years): During adolescence, young people experience rapid and often unpredictable changes. Growth spurts can cause temporary weight fluctuations that dramatically impact BMI calculations.

Hormonal surges, particularly during puberty, influence muscle development, fat distribution, and bone density. The teenage body is essentially a construction site, with continuous building and rebuilding that makes BMI interpretation challenging.

A teenager might show an elevated BMI during a growth spurt, only to see it normalize as height catches up to weight gain.

Adults (20-64 years): This life stage represents the most stable period for BMI interpretation. Young adults typically reach peak bone density and muscle mass in their twenties, providing a relatively consistent baseline for BMI calculations.

However, subtle changes begin around age 30, when metabolism starts its gradual decline. Adults in their forties and fifties may notice that maintaining the same weight becomes more challenging, even with identical lifestyle habits.

This metabolic slowdown averages 1-2% per decade, according to extensive research from major medical institutions.

Seniors (65+ years): Older adults face the most complex BMI interpretation challenges. Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass, becomes increasingly significant after age 65. Adults can lose 3-8% of muscle mass per decade after age 30, with acceleration after 60.

This muscle loss directly impacts BMI accuracy because muscle tissue is denser and weighs more than fat tissue. A senior citizen might maintain stable weight while actually losing muscle and gaining fat, creating a misleading BMI that appears healthy but masks concerning body composition changes.

The Science Behind Age-Related BMI Differences

Extensive research from the CDC, WHO, and Mayo Clinic demonstrates that metabolic changes, hormonal shifts, and tissue composition alterations make age-adjusted BMI interpretation essential for accurate health assessment.

Hormonal changes play a crucial role across all age groups. Teenagers experience dramatic hormonal fluctuations that affect growth patterns, appetite, and body composition.

Adults face gradual hormonal changes, with significant shifts occurring during menopause for women and andropause for men.

These hormonal transitions influence fat distribution, muscle maintenance, and metabolic rate. Seniors deal with declining levels of growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen, all of which affect body composition and weight regulation.

Metabolic rate changes create another layer of complexity. Basal metabolic rate peaks in young adulthood and gradually declines with age. This decline isn’t uniform across individuals and can be influenced by physical activity levels, muscle mass, genetics, and overall health status.

Understanding these metabolic changes helps explain why identical BMI values might indicate different health risks across age groups.

The relationship works as an interconnected system: BMI ↔ Body Composition ↔ Age ↔ Metabolic Rate ↔ Hormonal Status. Changes in any one factor inevitably affect the others, making age-adjusted interpretations crucial for meaningful health assessments and appropriate interventions.

Is BMI always accurate for different ages? Learn more about BMI limitations across age groups and when alternative measurements might provide better health insights.

How to Use the Age-Based BMI Calculator

Using an age-specific BMI calculator ensures you receive the most relevant and actionable health insights tailored to your life stage. These specialized calculators go beyond simple weight-to-height ratios to provide context-appropriate health assessments.

What You’ll Need for Accurate Results:

- Current weight (measured in pounds or kilograms)

- Height (measured in feet/inches or centimeters)

- Your specific age or age group selection

- Gender (affects muscle mass and body composition calculations)

- Activity level (influences interpretation recommendations)

Understanding the Difference: Age-Specific vs Standard BMI

Unlike a standard BMI calculator that applies universal categories regardless of age, age-adjusted calculators account for normal physiological changes throughout life.

Standard BMI calculators might flag a healthy 70-year-old as underweight when their BMI is actually appropriate for their age group, or conversely, might miss concerning body composition changes in a teenager whose BMI appears normal but reflects poor muscle development.

Age-specific calculators incorporate research-backed adjustments that consider developmental stages, metabolic changes, and age-appropriate health risks.

They provide more nuanced results that help users understand not just their BMI number, but what that number means for their specific life stage and health goals.

Use this tool if you’re unsure whether your BMI should be interpreted differently due to age-related body composition changes, if you’re concerned about weight changes that seem disproportionate to lifestyle modifications, or if you want to understand age-appropriate health targets for weight management.

How to Use Our BMI by Age Group Calculator

Select Your Appropriate Age Group:

Teenager (13-19 years): This calculator setting accounts for rapid growth spurts, developing body composition, and the natural weight fluctuations that occur during adolescence.

Teen calculations often use percentile rankings compared to same-age peers rather than absolute BMI categories, providing more appropriate health assessments during these developmental years.

Adult (20-64 years): Uses standard BMI categories with full adult ranges while accounting for gradual metabolic changes that occur throughout middle age.

This setting provides the most straightforward BMI interpretation, as adult body composition remains relatively stable during this life stage.

Senior (65+ years): Adjusts calculations for muscle loss, bone density changes, and age-related metabolic shifts. Senior calculations often suggest slightly higher BMI ranges as potentially healthy, recognizing that modest weight increases can be protective against frailty and illness in older adults.

Input Options Available:

- Metric system (kilograms, centimeters) for international users

- Imperial system (pounds, feet/inches) for users preferring traditional measurements

- Optional activity level assessment for more personalized recommendations

- Medical history considerations for specialized populations

Critical Medical Disclaimer: BMI serves as a screening tool, not a diagnostic instrument. It provides general health risk categories and population-level health insights but cannot assess individual health status, diagnose medical conditions, or replace comprehensive medical evaluation by qualified healthcare providers.

Age-Specific BMI Interpretations

Teenagers (13-19)

Teenage BMI interpretation requires exceptional care and specialized knowledge due to the complex physiological changes occurring during adolescence. This life stage presents unique challenges that make standard adult BMI categories inappropriate and potentially harmful if misapplied.

Understanding Why Teen BMI Fluctuates:

Growth spurts create temporary weight-to-height imbalances that can dramatically skew BMI readings. A teenager might experience rapid height increases followed by weight gain, or vice versa, creating BMI fluctuations that appear concerning but represent normal development patterns.

These growth patterns are highly individual, influenced by genetics, nutrition, physical activity, and hormonal development.

Hormonal changes during puberty affect every aspect of body composition. Testosterone increases muscle mass development in boys, while estrogen influences fat distribution in girls.

These hormonal surges occur at different rates and intensities among individuals, making peer comparisons often misleading. Growth hormone fluctuations can cause rapid changes in height, weight, and muscle development that temporarily distort BMI calculations.

Athletic development varies tremendously among teenagers. Some teens participate in intensive sports training that builds significant muscle mass, potentially elevating BMI despite excellent health and fitness.

Others might be naturally thin with lower muscle mass, showing lower BMI that doesn’t necessarily indicate health problems. Physical development during teen years is highly individual and should be assessed within the context of overall health and development patterns.

CDC Percentile Chart Approach:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention uses percentile charts rather than absolute BMI categories for teenagers. These charts compare individuals to peers of the same age and gender, providing more appropriate developmental context.

A BMI that might seem concerning in adult terms could be perfectly normal when compared to same-age peers experiencing similar developmental changes.

Parental Guidance and Professional Consultation:

Parents should never attempt self-diagnosis based solely on BMI calculations. Teenage health assessment requires professional evaluation that considers growth patterns, developmental stage, family history, nutritional status, and psychological factors.

Pediatricians and adolescent medicine specialists can interpret BMI within the broader context of adolescent development and identify when intervention might be necessary.

Inappropriate focus on BMI numbers during teenage years can contribute to eating disorders, body image problems, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. Professional guidance helps families understand normal development variations and when health concerns might warrant attention.

Learn more about healthy BMI ranges by age for comprehensive age-appropriate guidelines that consider developmental stages and individual variation.

Adults (20-64)

Adult BMI interpretation follows well-established categories developed through extensive population research, but even within this “stable” life stage, age-related considerations become increasingly important as adults progress through their twenties, thirties, forties, and beyond.

Standard WHO BMI Categories for Adults:

- Underweight: Below 18.5 – May indicate nutritional deficiencies, underlying health conditions, or eating disorders

- Normal weight: 18.5-24.9 – Associated with lowest health risks in most adult populations

- Overweight: 25.0-29.9 – Moderate increase in health risks, particularly for cardiovascular disease

- Obese Class I: 30.0-34.9 – Significant health risks requiring lifestyle intervention

- Obese Class II: 35.0-39.9 – High health risks often requiring medical intervention

- Obese Class III: 40.0 and above – Very high health risks typically requiring comprehensive medical management

Understanding Why Adult BMI Ranges Maintain Stability:

Adults between ages 20-40 experience minimal natural body composition changes under normal circumstances, making standard BMI categories most reliable and predictive for this population.

Peak bone density is typically achieved in the late twenties, muscle mass reaches its natural maximum in early adulthood, and metabolic rate remains relatively stable through the thirties.

However, important age-related considerations emerge as adults progress through middle age. After age 40, adults begin experiencing gradual muscle loss, typically 0.5-1% per year.

Metabolic rate starts declining more noticeably, making weight maintenance more challenging even with consistent lifestyle habits. Hormonal changes, particularly during perimenopause and menopause for women, can affect fat distribution and weight regulation.

BMI Limitations in Highly Active Adults:

Adults with significant muscle mass from regular strength training or athletic activities may register BMI values in the “overweight” or even “obese” categories despite excellent health profiles.

Muscle tissue weighs more than fat tissue, so individuals with high muscle-to-fat ratios can have elevated BMI without corresponding health risks.

These individuals typically have low body fat percentages, excellent cardiovascular fitness, and strong metabolic profiles that contradict their BMI classifications.

Age-Progression Considerations:

Adults approaching age 50 should begin considering additional health metrics beyond BMI alone. Waist circumference, body fat percentage, cardiovascular fitness, and metabolic markers become increasingly important for comprehensive health assessment.

The transition from “adult” to “senior” BMI interpretation typically begins in the late fifties to early sixties, depending on individual health status and physiological aging patterns.

Discover how BMI applies to athletes and when standard categories may not accurately reflect health status in highly trained individuals.

Seniors (65+)

Senior BMI interpretation represents the most complex and nuanced application of body mass index calculations. The physiological changes that accumulate throughout life reach their most significant impact during senior years, requiring careful consideration of multiple factors that influence both BMI accuracy and health implications.

Unique Physiological Considerations for Seniors:

Sarcopenia and Muscle Loss: Age-related muscle loss accelerates significantly after age 65, with some individuals losing 1-2% of muscle mass annually.

This muscle loss, termed sarcopenia, directly impacts BMI accuracy because muscle tissue is denser and weighs more than fat tissue.

A senior might maintain stable weight while simultaneously losing muscle and gaining fat, creating a BMI that appears unchanged but masks concerning shifts in body composition.

Bone Density Changes: Osteoporosis and general bone density reduction affect overall body weight and can influence BMI calculations.

Seniors with significant bone loss might show lower BMI that doesn’t accurately reflect their soft tissue composition or health status.

Medication Effects: Many seniors take multiple medications that can influence weight, appetite, water retention, and metabolic rate. These pharmaceutical effects can create BMI fluctuations that don’t necessarily reflect lifestyle changes or underlying health changes.

Chronic Condition Impacts: Age-related health conditions such as arthritis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and kidney problems can all influence weight, body composition, and the relationship between BMI and health outcomes.

Research-Based Insights for Senior BMI:

Multiple studies published in geriatric medicine journals suggest that slightly elevated BMI ranges may be optimal for seniors.

Research from the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society indicates that BMI ranges of 25-30 may provide protection against frailty, improve recovery from illness, and correlate with better survival rates in older adults.

This “obesity paradox” suggests that modest weight reserves can be beneficial during health challenges that commonly affect seniors.

The protective effect of slightly higher BMI in seniors may relate to nutritional reserves during illness, better muscle mass maintenance, and improved recovery capacity.

However, this doesn’t mean that significant obesity is beneficial; rather, it suggests that the “ideal” BMI range shifts upward with age.

Comprehensive Health Assessment Beyond BMI:

Seniors should combine BMI measurements with multiple additional health indicators for comprehensive assessment. Waist circumference helps identify abdominal obesity that carries particular health risks.

Muscle strength assessments, such as grip strength tests, can identify sarcopenia that BMI might miss. Functional capacity evaluations, including balance tests and mobility assessments, provide crucial information about overall health that BMI cannot capture.

Regular monitoring of bone density, cardiovascular health, metabolic markers, and cognitive function provides a complete health picture that goes far beyond what BMI alone can reveal.

The goal for seniors should be maintaining functional independence and quality of life rather than achieving specific BMI targets.

Explore specialized BMI guidelines for seniors for detailed age-appropriate health assessments and comprehensive approaches to healthy aging.

Download and share this comprehensive reference chart for quick, evidence-based age-appropriate BMI guidance throughout all life stages.

BMI for Teens vs Adults vs Seniors

Comprehensive Side-by-Side Analysis:

| Assessment Factor | Teens (13-19) | Adults (20-64) | Seniors (65+) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Health Focus | Growth pattern monitoring, developmental appropriateness | Weight maintenance, chronic disease prevention | Muscle preservation, functional capacity maintenance |

| BMI Calculation Reliability | Moderate (growth spurts affect accuracy) | High (most reliable life stage) | Moderate (muscle loss affects interpretation) |

| Key Health Concerns | Eating disorders, body image issues, nutritional adequacy | Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome | Frailty, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, functional decline |

| Recommended Actions | Monitor growth trends, avoid restrictive dieting, promote balanced nutrition | Maintain active lifestyle, monitor gradual changes, prevent chronic disease | Focus on strength training, ensure adequate nutrition, preserve independence |

| Professional Consultation | Pediatricians, adolescent medicine specialists | Primary care physicians, nutritionists, fitness professionals | Geriatricians, physical therapists, registered dietitians |

| Measurement Frequency | During regular pediatric visits, avoid obsessive monitoring | Annual check-ups, more frequent if health concerns arise | Every 6 months or as medically recommended |

| Additional Assessments | Growth percentiles, developmental milestones, nutritional status | Body fat percentage, cardiovascular fitness, metabolic markers | Functional capacity, muscle strength, bone density, cognitive status |

Detailed Scenarios When BMI May Mislead:

Highly Active Teenagers: Student athletes, particularly those involved in strength sports or activities requiring significant muscle development, may show elevated BMI readings that don’t reflect health risks.

A teenage football player or gymnast might register BMI in the “overweight” category due to muscle mass while maintaining excellent cardiovascular health and appropriate body fat levels.

Older Adults with Sarcopenia: Seniors experiencing significant muscle loss might maintain BMI in the “normal” range while actually having concerning body composition changes.

These individuals might have lost substantial muscle mass and gained fat tissue, creating health risks that BMI doesn’t detect. This scenario requires additional assessments like body composition analysis and functional testing.

Post-Menopausal Women: Hormonal changes during and after menopause can significantly affect weight distribution, metabolic rate, and body composition.

Women might experience BMI increases despite maintaining similar lifestyle habits, reflecting normal physiological changes rather than health problems requiring dramatic intervention.

Adults with High Muscle Mass: Individuals engaged in regular strength training, manual labor, or sports requiring significant muscle development might show elevated BMI despite excellent health profiles. These individuals typically have low body fat percentages and excellent metabolic health that contradicts their BMI classification.

Compare BMI vs body fat percentage to understand when alternative measurements provide better health insights and more accurate assessment of health status.

Should Seniors Use BMI?

The question of BMI usefulness for seniors requires careful consideration of both its limitations and continued value when properly interpreted.

While BMI becomes less accurate with age, it remains a useful screening tool when combined with other health assessments and interpreted within appropriate age-related contexts.

Detailed BMI Limitations in Elderly Populations:

Muscle vs Fat Distinction Problems: BMI cannot differentiate between muscle mass and fat tissue, a limitation that becomes particularly problematic with age-related muscle loss.

Two seniors with identical BMI might have vastly different health profiles—one maintaining good muscle mass and the other experiencing significant sarcopenia with increased fat tissue.

Functional Health Status Disconnect: BMI doesn’t reflect functional capacity, mobility, strength, or independence levels that are crucial health indicators for seniors.

A senior with slightly elevated BMI who maintains active lifestyle and functional independence might be healthier than a senior with “normal” BMI who is sedentary and frail.

Chronic Condition Interactions: Many age-related health conditions affect weight and body composition in ways that complicate BMI interpretation.

Heart failure might cause fluid retention, kidney disease can affect protein balance, and medications might influence appetite and metabolism, all creating BMI fluctuations unrelated to nutritional status or lifestyle factors.

Bone Density Considerations: Osteoporosis and bone density loss can significantly affect total body weight, potentially creating misleadingly low BMI readings that don’t reflect soft tissue composition or nutritional status.

When Seniors Should Look Beyond BMI:

Highly active seniors who maintain regular exercise routines, particularly those including strength training, should consider BMI alongside functional assessments and body composition measurements.

Their health status might be excellent despite BMI readings that seem suboptimal by standard measures.

Seniors dealing with chronic conditions affecting weight, such as heart disease, kidney problems, or diabetes, need comprehensive medical evaluation that goes far beyond BMI calculations.

These conditions create complex interactions that require professional medical interpretation.

Individuals who have experienced significant muscle loss should focus on functional capacity, strength measurements, and nutritional assessments rather than BMI alone. Recovery and maintenance of muscle mass becomes more important than achieving specific BMI targets.

Evidence-Based Alternative Health Assessments:

Waist-to-Hip Ratio: Provides information about fat distribution that’s particularly relevant for cardiovascular and metabolic health risks in seniors.

Functional Capacity Testing: Assessments of walking speed, balance, chair-stand tests, and activities of daily living provide crucial information about health status and independence prospects.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Professional evaluations that consider cognitive function, social support, medication effects, and overall health status provide much more complete health pictures than BMI alone.

Muscle Strength Testing: Grip strength, leg strength, and other functional strength measures can identify sarcopenia and frailty risks that BMI misses entirely.

Professional Medical Recommendation: Seniors should always work with healthcare providers experienced in geriatric medicine for comprehensive health assessment and personalized recommendations.

BMI should be one component of broader health monitoring that includes functional, cognitive, social, and medical factors affecting overall wellbeing and quality of life.

Learn more about BMI accuracy concerns and discover when alternative health metrics provide more appropriate and actionable health information for seniors.

How to Improve Your BMI at Any Age

Achieving and maintaining optimal BMI requires different approaches at different life stages. Understanding these age-specific strategies helps individuals make appropriate choices that support both immediate health goals and long-term wellbeing throughout life transitions.

Detailed Strategies for Teenagers:

Nutritional Focus Without Restriction: Teenagers require adequate nutrition to support rapid growth and development.

Rather than focusing on caloric restriction, teens should emphasize nutrient-dense foods that provide essential vitamins, minerals, proteins, and healthy fats needed for optimal development.

Restrictive dieting during adolescence can interfere with normal growth patterns and contribute to eating disorders.

Physical Activity Integration: Regular physical activity should focus on enjoyment, skill development, and establishing lifelong healthy habits rather than intense weight loss efforts.

Sports participation, recreational activities, and family-based physical activities help teens develop positive relationships with exercise while supporting healthy development.

Sleep and Stress Management: Adolescents require 8-10 hours of sleep nightly for optimal growth and development. Poor sleep patterns can disrupt hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism, contributing to weight management challenges.

Stress management through healthy activities, social support, and appropriate academic balance supports overall health.

Family-Based Approaches: Successful teen health improvement requires family involvement and support. Families should focus on creating healthy home environments with nutritious food options, regular meal patterns, and active lifestyle choices that benefit everyone rather than singling out individual family members.

Comprehensive Strategies for Adults:

Sustainable Fitness Integration: Adults benefit from combining cardiovascular exercise, strength training, and flexibility work into regular routines that can be maintained long-term. The goal should be establishing consistent exercise habits that fit into adult lifestyle demands including work, family, and social responsibilities.

Gradual Behavior Modification: Research supports making small, sustainable changes rather than dramatic lifestyle overhauls that are difficult to maintain. Adults should focus on gradual improvements in nutrition quality, portion sizes, physical activity levels, and stress management that can be integrated into existing life patterns.

Metabolic Considerations: Adults, particularly those over 40, should account for gradual metabolic changes when setting realistic goals and timelines. Weight management strategies that worked in twenties might need adjustment to accommodate slower metabolic rates and changing hormonal profiles.

Professional Support Integration: Adults benefit from working with registered dietitians, certified fitness professionals, and healthcare providers to develop personalized strategies that consider individual health status, medical conditions, medications, and lifestyle factors.

Specialized Strategies for Seniors:

Muscle Preservation Priority: Seniors should prioritize maintaining and building muscle mass through regular resistance training, adequate protein intake, and physical activities that challenge strength and balance.

Muscle preservation becomes more important than weight loss alone for maintaining independence and quality of life.

Nutritional Adequacy Focus: Older adults require careful attention to nutritional adequacy, ensuring sufficient protein intake (typically 1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram body weight), adequate vitamins and minerals, and appropriate hydration. Weight management should never compromise nutritional status.

Functional Fitness Emphasis: Exercise programs should focus on maintaining and improving functional capacity, including balance, flexibility, strength, and endurance needed for daily activities. Programs should be designed with safety considerations and may need modification for existing health conditions or physical limitations.

Medical Integration: Seniors should work closely with healthcare providers to ensure weight management efforts are appropriate for existing health conditions, don’t interfere with medications, and support overall health goals rather than focusing solely on BMI targets.

Universal Principles Across All Ages:

Gradual, Sustainable Changes: All age groups benefit from making small, consistent changes that can be maintained over time rather than dramatic short-term interventions that are difficult to sustain.

Multiple Health Metric Monitoring: Rather than focusing exclusively on BMI or weight, individuals should monitor various health indicators including energy levels, sleep quality, physical capacity, mood, and overall wellbeing.

Professional Guidance Integration: Working with qualified healthcare providers, registered dietitians, and certified fitness professionals helps ensure approaches are safe, appropriate, and effective for individual circumstances.

Long-term Health Focus: Decisions should be made with consideration for long-term health outcomes rather than short-term appearance goals, supporting sustainable health improvements throughout life transitions.

Discover comprehensive, evidence-based strategies for how to lower your BMI safely and effectively with approaches tailored to your specific life stage and health goals.

FAQs About BMI and Age

1. Does BMI calculation change with age? The mathematical formula for calculating BMI remains constant (weight in kg divided by height in meters squared), but the interpretation of results should definitely change with age. Body composition changes mean identical BMI values represent different health risks and require different responses at different life stages.

2. Is a BMI of 25 considered healthy for seniors? Yes, research increasingly suggests that BMI ranges of 25-30 may be optimal for seniors rather than the standard 18.5-24.9 range. Studies indicate that slightly higher BMI can provide protection against frailty, improve recovery from illness, and correlate with better survival rates in older adults.

3. Why does my BMI seem to increase after age 40 even with the same lifestyle? Metabolic rate naturally decreases by approximately 1-2% per decade after age 30, and muscle mass begins declining around the same time. These physiological changes mean that maintaining the same weight requires either reducing caloric intake or increasing physical activity to compensate for slower metabolism.

4. Should teenagers be concerned about BMI readings in the overweight range? Not necessarily, and obsessive focus on BMI during adolescence can be counterproductive. Teenage BMI fluctuates significantly due to growth spurts, hormonal changes, and developmental variations. Healthcare providers use percentile charts comparing teens to same-age peers rather than adult BMI categories.

5. How accurate is BMI for seniors compared to younger adults? BMI accuracy decreases with age due to muscle loss (sarcopenia), bone density changes, and altered body composition. Seniors should use BMI alongside other health measures including waist circumference, functional capacity assessments, and muscle strength evaluations for comprehensive health monitoring.

6. Can BMI predict health risks differently across age groups? Absolutely. The same BMI carries dramatically different health implications across age groups. Higher BMI poses greater cardiovascular and metabolic risks in young adults, while moderately elevated BMI may actually provide protective benefits against frailty and illness recovery in seniors.

7. What’s considered the healthiest BMI range for my specific age? Teens should focus on growth percentiles and developmental appropriateness rather than absolute BMI numbers. Adults typically target the standard 18.5-24.9 range, while seniors may benefit from slightly higher ranges of 23-28, depending on individual health factors, muscle mass, and functional status.

8. Should I use regular BMI calculators or age-specific versions? Age-specific calculators provide significantly more relevant and actionable health insights by accounting for normal physiological changes throughout life. They offer better guidance for health decisions than standard BMI calculations that ignore age-related body composition changes.

9. How often should I monitor my BMI at different life stages? Monitoring frequency should match health needs and life stage characteristics. Teens should check during regular pediatric visits without obsessive daily monitoring. Adults benefit from annual assessments or more frequent monitoring during active weight management. Seniors should monitor every 6 months or as recommended by healthcare providers.

10. Does age-related muscle loss make BMI completely unreliable for seniors? Not completely unreliable, but significantly less accurate when used alone. Muscle loss can make BMI appear healthier than actual body composition suggests. Seniors should combine BMI with muscle strength assessments, functional capacity tests, and comprehensive health evaluations for accurate health status understanding.

11. At what age should I start using senior-specific BMI interpretations? The transition typically occurs gradually between ages 60-70, depending on individual health status and physiological aging patterns. Most health professionals begin applying senior-specific considerations around age 65, but individuals with significant health conditions or advanced aging changes might benefit from adjusted interpretations earlier.

12. Can hormonal changes affect BMI interpretation across age groups? Yes, hormonal changes significantly impact BMI interpretation throughout life. Puberty affects teenage BMI through growth and development hormones. Adult hormonal changes, particularly during menopause and andropause, influence fat distribution and metabolic rate. Senior hormonal changes affect muscle maintenance and metabolic function, all requiring adjusted BMI interpretation approaches.

Find comprehensive answers to additional questions in our detailed BMI FAQ section, covering topics from basic calculations to complex health considerations across all life stages.

Ready to discover your healthiest BMI range for your age? Try the calculator above or explore more evidence-based guides tailored to your specific health goals and life stage. Take the first step toward age-appropriate health optimization today.